Seeking Compensation for Formerly Separated Families

The Ms. L. litigation and settlement prohibit indiscriminate family separation at the border; make special immigration relief available to formerly separated families; and entitle class members to legal assistance, mental health care, and other benefits. But the Ms. L. case did not address whether the families should receive monetary compensation for the harms they suffered. To address this question, families throughout the country have filed more than 40 cases seeking compensation under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Lowenstein filed three of these cases.

We have long represented the three families in their immigration cases. One father-son pair has already won asylum, among the first of the separated families to have surmounted this hurdle. Now, all three families have sued the government for money damages for the harms they suffered, and continue to suffer, as a result of their separations.

■■■■■

“Beatriz” and her then 3-year-old son “Manuel” fled El Salvador in May 2018 after a local gang threatened them. In late May, they entered the United States through an authorized checkpoint, where they were inspected and detained. Two days later, officers with United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) loaded Beatriz and Manuel into the backseat of a jeep and drove them to the parking lot of the Port Isabel Detention Center in southern Texas. There, an officer grabbed Manuel and his small backpack out of Beatriz’s lap and placed him in the backseat of another jeep. As the officers carried him away, Manuel began screaming and hitting them. Delayed in his speech, he cried “Mama,” using that word for the first time in his panic. After a few minutes witnessing Manuel’s anguish and hearing his screams, Beatriz got out of the jeep that had transported them and hurried over to the other jeep where the officers had put Manuel. The officers refused to let Beatriz inside to hold her son. Instead, she pressed her hands against the window and offered Manuel words of comfort through the glass, as he continued crying, hitting the window, and calling out for her. After several minutes, a couple of officers drove off with Manuel while others handcuffed Beatriz and marched her into the detention center. Beatriz remained in detention in Texas while Manuel was flown to a children’s detention facility in New York City. They did not see each other again for 42 days. Beatriz was not prosecuted for illegal entry, nor could she have been given that she and Manuel committed no crime by presenting themselves at an authorized checkpoint and claiming asylum.

■■■■■

“Jacob” and his then 4-year-old daughter “Leya” fled Honduras to escape violence and death threats from a local gang. After crossing the Rio Grande with Leya on his shoulders in early April 2018, Jacob approached CBP officers and asked for help. Jacob turned over their documents, including Leya’s birth certificate naming him as her father, as well as his Honduran identification card. The officers searched them, confiscated their few belongings, and drove them to the Rio Grande Valley Processing Center. In the middle of that night, CBP officers ripped Leya from Jacob’s arms and carried her away as she screamed for her father. Jacob got on his knees and begged the officers to bring her back. They responded by accusing Jacob of having kidnapped his daughter, despite proof of parentage, and told him that he would not see her again. Without telling Jacob where they had taken his little girl, officers transferred him to several immigration detention centers over their three-month separation. Other officers flew Leya to a detention facility in Michigan. Leya describes the officers as having drugged and kidnapped her. Jacob and Leya did not see each other again for 93 days. The government never prosecuted Jacob for any criminal offense.

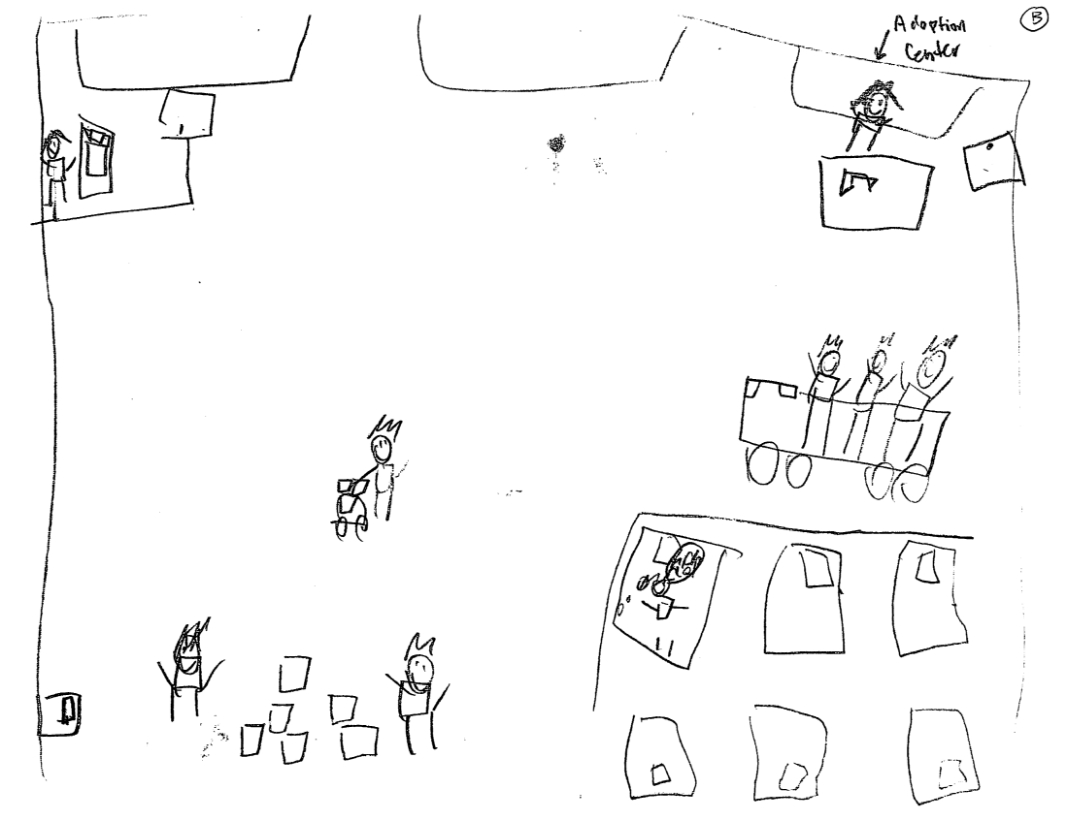

Photo by Bernard DeLierre

■■■■■

“Rafael” and his then 12-year-old son “Orlan” fled Guatemala in response to escalating death threats from a local governing body that sought to deprive Rafael’s family of their right to ancestral, indigenous lands. In June 2018, they entered the United States and walked toward the first CBP officers they saw, intending to explain that they were fleeing persecution (the basis for their grants of asylum three years later). The officers threatened to shoot them and announced their intention to take Orlan away from Rafael. Orlan and Rafael were detained together for two days and then separated. Rafael was transferred to the custody of the U.S. Marshals Service, which transported him and other parents to the El Paso County Jail. The next morning, CBP transferred Orlan to the Clint Border Patrol Station, less than an hour’s drive from El Paso. Meanwhile, the U.S. Marshals Service transported Rafael to federal court where, on the advice of a lawyer, he pled guilty to misdemeanor illegal entry in hopes that doing so would lead to speedier reunification with his son. The court sentenced him to time served, after which he was temporarily held in a facility in El Paso. Although Orlan was then in a nearby CBP facility, the government did not reunify him with his father and did not inform either one of the other’s whereabouts. Instead, immigration officers transported them in opposite directions: Rafael to New Mexico and Orlan to East Texas, nearly 1,000 miles apart. Rafael and Orlan did not see each other for 37 days.

The government provided the parents and children only limited or no information about each other and facilitated only inadequate communication or none at all. More than five years later, the parents cannot talk about these events without breaking down, and the children are haunted by the experience.

After the firm filed FTCA cases on behalf of the three families, the government moved to dismiss. The government argued first that the court lacked jurisdiction under various exceptions to the FTCA, and second that the plaintiffs had not alleged sufficient facts to support the torts they claimed the government had committed. The court rejected these arguments, finding “each of the FTCA exceptions raised in [the government’s] Motions to Dismiss either inapplicable or presently lacking in factual support.” The court also reviewed with care the 10 different torts the plaintiffs alleged and found a legal and factual basis in the complaints for all but one of them.

The cases are now moving into discovery, the phase during which the parties exchange information to amass evidence for their claims or defenses. This process will take a year or more before the cases head to trial, unless they settle along the way.

Photo by Bernard DeLierre