Providing Second Chances Through Clemency

Clemency has been a dramatically underutilized tool in New Jersey, with only 105 people receiving clemency between 1994 and 2022. But on Juneteenth in 2024, Governor Murphy announced a plan to change that. He issued Executive Order No. 362, which establishes certain categories of clemency applications that will receive expedited review. Among the categories of applications eligible for expedited review are those from individuals who are serving sentences that reflect an excessive trial penalty (i.e., where the sentence after trial far exceeds the plea offer) and people whose convictions would have resulted in a less severe sentence under current law or policy.

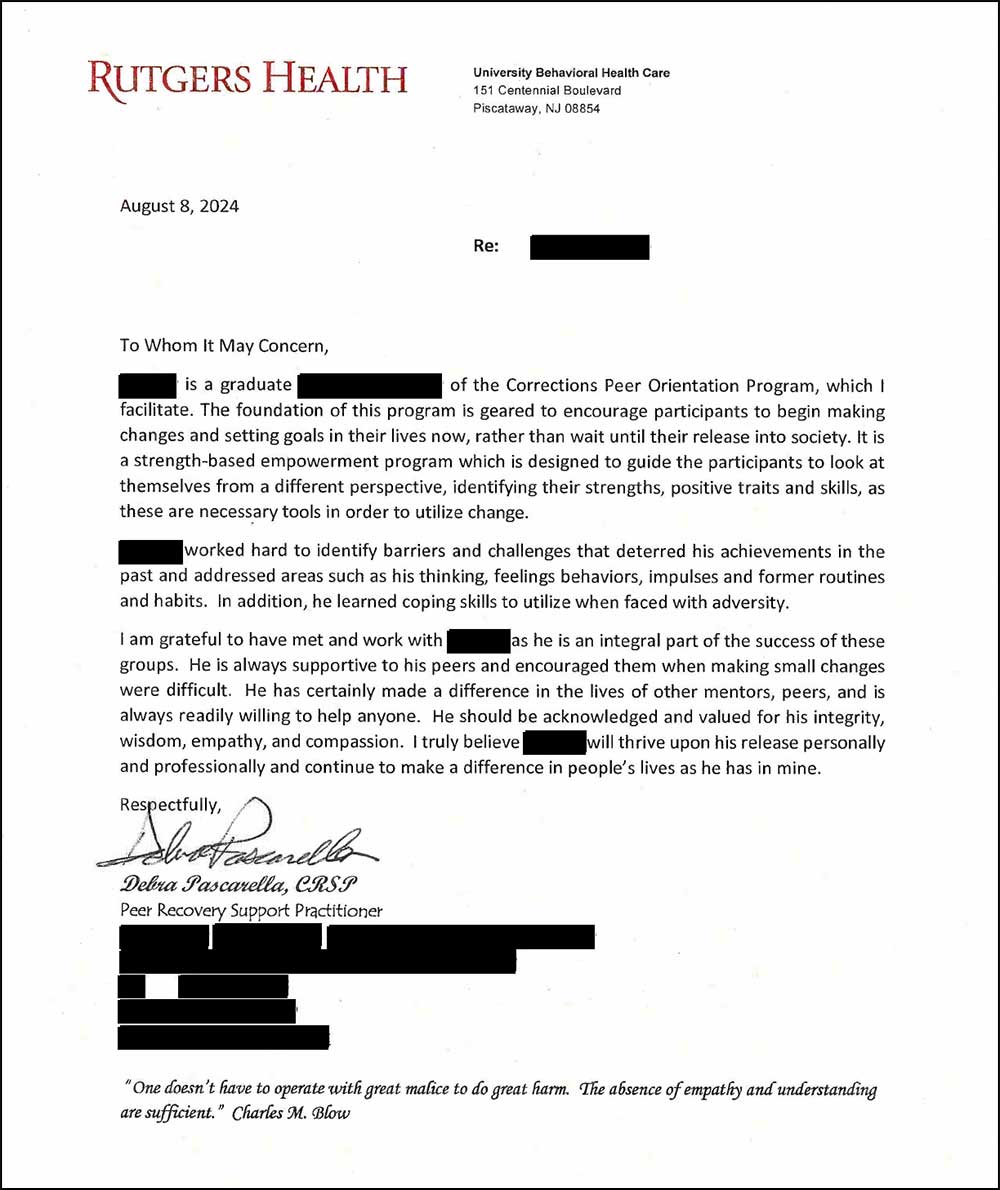

The firm immediately began working with the ACLU of New Jersey, which had been at the forefront of pushing for the expanded use of clemency as a tool to combat systemic injustices. In partnership with the ACLU of New Jersey, the firm has filed two clemency petitions and is preparing others for individuals who qualify for expedited consideration under the Executive Order. Clemency is about more than just mercy. It is a recognition that young people—even young people convicted of very serious crimes—are capable of redemption and change.

Please click below to learn more about our clemency clients.

Clemency is a recognition that young people are capable of redemption and change.

- "Johnny"

- “JANE”

"Johnny"

When Johnny was 19, he was a functionally illiterate person who had been living on his own for five years, supporting himself by selling drugs. He and some friends planned to rob a drug dealer. During the robbery, Johnny shot and killed the dealer, and he was arrested, tried, and convicted. At sentencing, instead of finding Johnny’s youth to be a mitigating factor—as modern sentencing law requires—the judge relied on the now-debunked “super-predator theory,” which called for the harsh sentencing of young people, particularly young Black boys. The judge called Johnny a “malevolent missile of mayhem” and sentenced him to life in prison with a mandatory minimum sentence of 40 years.

Some people would respond to a judge imposing such a severe sentence with bitterness and anger, but Johnny responded differently: He sought to prove the judge wrong. He first learned to read; then, after he obtained his high school diploma, he began tutoring other incarcerated people who were struggling with illiteracy. But he did not stop there—he obtained an associate degree; earned a bachelor’s degree, summa cum laude; and he has even completed coursework for a master’s degree in theology. He is putting his education to good use: He has been a prison paralegal, a frequent preacher, and a volunteer tutor, serving other incarcerated people.

"Jane"

Jane was convicted for her role in a robbery-murder more than 30 years ago. Jane was only months past her 18th birthday when she participated in a robbery in which her older co-defendants killed the victim. Prosecutors recognized Jane’s diminished culpability based on her age and her more limited role in the crime—they called her a follower and acknowledged that she had not actively participated in the killing—and offered her a plea bargain under which she would serve 30 years in prison. She turned down the offer, went to trial, was convicted, and was sentenced to life in prison, with a mandatory minimum term of 40 years.

While incarcerated, Jane has transformed herself. She entered prison as a particularly immature 18-year-old without a high school education. In the past three decades, she, like Johnny, has received a high school diploma, an associate degree, and—with highest honors—a Bachelor of Arts from Rutgers University. And her transformation is not limited to educational attainment; she is now a well-respected leader among her peers, providing tutoring and mentorship. She is also a published author.

When Jane was sentenced, courts had no mechanism to recognize that an 18-year-old was less mature and, therefore, less culpable than an older person. But today, New Jersey sentencing law does just that, providing for consideration of youth as a mitigating factor for people under 26. Had Jane been sentenced under the current scheme—or had she accepted the plea bargain—she would have already been released.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images